Three New Ways of Looking at the American West

What would it be like to live in the American West minus John Wayne, the Yellowstone television series, and the whole cowboy-and-Indian mythic complex?

What stories would we tell ourselves if we weren’t chained to that distorting epic of how White settlers battled the elements and the savages to create a city on a hill west of the Mississippi River?

How could we replace those violent fantasies of remaking a vast geography populated with diverse nations that claimed the place before any of “us” arrived?

An answer can be found in three books recently or soon to be published on Montana history and culture. The stories they tell take us inside creative lives and inventive historical actors who subvert the tiresome but seemingly indestructible cliches of the American West.

O. Alan Weltzien, Rick Newby, and Sally Thompson build on at least fifty years of determined efforts to recast western settlement not as a triumphalist narrative but as a montage of conflicting, difficult, sometimes beautiful, often heartbreaking stories. The New Western History launched in the late 70s and early 80s directly challenged manifest destiny as the definitive account of westward migration.

Articulated with unusual candor and wit by Patricia Limerick’s The Legacy of Conquest (1987), this “new” reading was itself built on the brilliant work of cultural historians such as Richard Slotkin (Regeneration through Violence and The Fatal Environment), regional historians such as Montana’s own Joseph Kinsey Howard and K. Ross Toole, regional novelists such as Wallace Stegner, A.B. Guthrie Jr., and Mildred Walker, and especially Native American writers such as N. Scott Momaday, James Welch, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Joy Harjo. Collectively the revisionists revealed western settlement not as some seamless, inevitable process of cultural transformation but as a violent imposition of a distinctly American economic and political system on peoples and places overwhelmed by force and demography.

Despite this ardent, eloquent effort, the cowboy myth remains largely unshaken. On a recent trip to Alaska I was lectured by a traveler from California that Yellowstone paints a pretty, dramatic picture of my home and I should embrace the branding opportunity. Russell Rowland, author of In Open Spaces and Fifty-Six Counties, has analyzed this amazing persistence with the insight of someone who helped out on his grandparents’ hardscrabble ranch in southeastern Montana:

Since we’re on the topic of Yellowstone, another thing that galls me about that show is that is resurrects the same old stereotype that the way men deal with conflict in this region is through posturing and/or violence. It’s an old trope that writers from the West have been trying to overcome for decades, so every time another show or film comes along and trots out these old cliches, it really makes me angry because I think a lot of our mental health issues have been perpetuated by these cliches.1

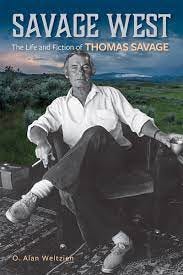

Imagine growing up in the cowboy world of early twentieth-century Montana and Idaho, compelled to conform to the macho stereotype, only to see through the cliches with lucid irony. Imagine a young man skilled in all ways of working a ranch yet living a double life as a gay adolescent, unusually gifted in literature and music, forced to pretend the cowboy myth holds. Imagine then that promising writer turns out to be one of the true originals in Western American literature, though often ignored by the region’s readers and critics, living at a far remove in Maine to gain perspective on a distorting life that summoned pain and regret.

The writer Thomas Savage lived out these contradictions and disappointments. Weltzien has helped rescue him from obscurity through a remarkable biography, Savage West: The Life and Fiction of Thomas Savage (University of Nevada Press, 2020). Having taught at the University of Montana Western for thirty years in the very town where Savage went to high school, Weltzien shows uncommon sympathy for this almost forgotten writer. Through careful study of Savage’s novels, journals, and correspondence, he reveals a deeply divided human being, aware from an early age of his intellectual gifts but recognizing they did not conform to the harsh physical reality of rural Western life. The result is highly original if deeply sad fiction:

In the eight novels set in southwestern Montana and Idaho’s Lemhi River Valley, Savage wields an acidic brush, one that goes against the grain of triumphal stories of white pioneers and their prospering or floundering descendants. Savage prefers anti-heroic, acerbic flavors. His stylistic wit and play, especially his essayistic interludes, expose grim realities and lonely spaces: spaces swollen by gender stereotypes that precluded, for the most part, sexual minorities such as himself. (p. 4)

Savage excelled at showing how the Western American myth warped young men’s psyches, leading to lacerating passive aggression and self-harm. The Power of the Dog, arguably his best novel and one converted to an Oscar-winning film by Jane Campion, features the acidic ranch foreman Phil Burbank. Internally riven by his sexual attraction to men, Phil channels his self-loathing into sadistic cruelty toward others, especially his brother’s wife and her son by another marriage. That cruelty sets in motion a chain of tragic events that demonstrates with little sentimentality how the cowboy myth kills. Savage’s novels still seem radically new for they overturn archetypes of Western bravado deeply encoded in our collective imagination.

To call Newby’s forthcoming collection of essays new may seem puzzling at first, since he gathers his exquisite studies of Montana literature, music, and visual arts from the past forty-seven years. Yet A Regionalism That Travels: Writings on (Mostly) Montana Arts, 1975-2022 (Drumlummon Institute, March, 2024) reads as fresh and revelatory. Newby advocates for “cosmopolitan regionalism” or, in the charming title of his collection, a regionalism that travels. Montanans may hew close to the reality of their Western lives but can remain open to cultural possibilities gathered from near and far. His essays return often to artists who inhabit this place yet show the curiosity and courage to embrace modes, styles, and concepts drawn from sophisticated outlanders.

No essay captures Newby’s “dynamic provincialism” as memorably as “The Montana-Paris Axis, or Unpacking My Grandfather’s Library: On the Track of a Bookish Tradition.” First published in Writing Montana: Literature Under the Big Sky (still my favorite book on Montana’s literary history), this essay became an instant classic, one of the must-read texts about my home state. Above all it is an appeal to allow the region’s artists to break out of the dominant Western American story to enact their distinctive visions:

But still, there’s one myth that hasn’t wholly died. . . . [T]he Montana writer shouldn’t depict a reality that strays too far from a generally accepted vision of what Montana might be: rough and ready, barely literate, beautiful but still . . . the ultimate frontier. . . . This self-imposed know-nothingism, a kind of censorship from within, has masked the very real sophistication of Montana’s artists, allowing them to “pass” as authentic westerners, but all too often preventing them from being wholly themselves.

This is Savage’s Phil Burbank attempting to write or paint or work clay. Concealing the artistic self splits the psyche and distorts the work, depriving Westerners of revealing accounts of their messy contemporary lives.

To counteract that self-defeating repression Newby traces a genealogy of bookishness in the place that became Montana, encompassing Native Americans, fur trappers, early settlers such as John Owen and Granville Stuart, the visionary Indigenous writer D’Arcy McNickle, the Butte provocateur Mary MacLane, and his own grandfather:

When, a few years back, I inherited two boxes of Jack Crowe’s books and his beautiful bookcase, I felt myself coming home in some deep sense. As I opened the boxes and wandered among the dusty volumes, I sensed my bookish grandfather at every turn, his bald head bent over a book, his slender hands, his quiet presence, just as in those comforting childhood moments when I felt him beside me, the two of us—a kindly ghost and a young boy avid to live—reading from the same page.

Newby stocks his grandfather’s beautiful bookcase with Montana’s diverse literary creations and discovers texts “all working together to offer us multiple histories and inventions of an actual culture—our own.”

Thompson compels Westerners to reverse perspective on the “discovery” legends, including the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Father Pierre-Jean De Smet’s missionary work in the northern Rockies. Her forthcoming book, Disturbing the Sleeping Buffalo: 23 Unexpected Stories that Awaken Montana's Past (Farcountry Press, March, 2024), gathers stories from her forty years as a public anthropologist to reveal how this place looked from Indigenous and women’s perspectives. Building on her ground-breaking People Before the Park: The Kootenai and Blackfeet before Glacier Park (2015), she advocates for an original kind of scholarship that combines conventional archival searches with attention to the oral stories passed down through tribal nations. She shows that locals can learn far more by combining research with deep relationships with Indigenous witnesses, creating trust and respecting which stories can be shared with a wider public:

Through a wide variety of projects, I learned from Native Montanans different perspectives about our shared history, our values, and our ways of knowing. I learned to respect the important truths held in oral history. Descendants of homesteaders taught me about the decades of transition, when the dominant story shifted from Native to White. From the historical record, I learned to dig deep, to read between the lines, and to question what is missing. And to better understand it all, I meandered along the old trails, and tried to imagine Montana as it was, long before we were born. After more than four decades, I have accumulated a large story trove.

The result is a set of exciting, wide-ranging stories that immerse readers in “unexpected” events among diverse tribal nations, including the Blackfeet, Assiniboine, A’aninin, Apsaalooke, and Kootenai. Her chapters often read as detective stories since the determined anthropologist travels unfamiliar paths to uncover a tangible remnant of De Smet’s journeys through the Rockies or to follow an Indigenous woman long obscured by the “heroic” accounts of White men.

Perhaps no story demonstrates Thompson’s sensitivity and persistence so clearly as her identifying and helping relocate a native child uncovered during excavation for a Missoula grocery store in 1950. Working under NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act), she seeks clues about the child’s birth family and tribe. I won’t spoil the surprise by revealing Thompson’s discoveries, but her insights will move the reader: “This unraveling world was the one the little girl had been born and buried into. She was somebody’s daughter.” This empathetic moment typifies Thompson’s deeply humane method.

Weltzien, Newby, and Thompson take us inside Western American lives through careful research and perceptive analysis. They shatter the panoramic vision of the American West to help us realize the actual day-to-day lives of gifted but troubled human beings who inhabited this place. They overcome the aggrandizing myth-making by walking in their writing subjects’ shoes, whether living in Thomas Savage’s hometown or sampling a grandfather’s library or recreating the life of an Indigenous child buried in Missoula. These writers substitute the granular and authentic for fantasy. In the process they can help contemporary Westerners perceive their own complex lives, to break the frame created by legend to see what’s actually happening. In this way these three writers can enable us to confront our deepest challenges, personal and political. It’s long past time we get real.

Todd Wilkinson, “Why 'Yellowstone' The TV Show Ain't The Real Montana (Or Wyoming, Or The West).” Mountain Journal, May 31, 2023, online edition.

Great piece, Ken. And thank you for the shout-out! But I'm especially glad to see you feature Alan's book here.

Working in construction management, hiring and firing young men with high school educations, or less, I spent a considerable amount of time explaining that being a man didn't have anything to do with the size of your gun or the color of your skin. The cowboy-and-Indian myth carried over into their daily lives. I repeated some admonitions over and over, "You can't work for me if you beat your wife, you cannot use racial epithets, even if you and I are alone," and my favorite, "No, you can't bring your gun to work."