Saved by Sondheim

I woke with a start in the middle of the night this past week, a song in my ear. As the petulant man-child takes a wrecking ball to our democracy, an elusive melody sang to me, a chorus of lush voices rising with the words “Sunday. . . Sunday. . . Sunday.” Stephen Sondheim had come to the rescue. I was immersed in the masterpiece that concludes Acts One and Two of Sunday in the Park with George.

Let’s concede that Sondheim is not to everyone’s taste. Not long ago two acquaintances, for reasons unknown, blurted out, “We can’t stand Sondheim.” I took a deep breath and asked why and as best as I can recall they declared him too clever by half, lacking heart and respect for American myths and traditions. Clearly my interlocuters were more in the Rodgers and Hammerstein camp (though playgoers often miss surprising nuances in their plays).1

I first encountered the New York music man around 1980 when my friend Chris Wheatley, my go-to scholar of American theater, told me Sondheim revolutionized the musical with A Little Night Music. I immediately went out to get the original cast recording on vinyl (ah, those innocent pre-Internet days) and was utterly charmed by the wit and sweet pain of the play. This erotic farce has much to teach about regret, longing, and finding compensations as we age. How could a lyricist compact so much insight into songs? (No wonder I went out of my way to see Bernadette Peters play the lead role in a 2010 revival on Broadway).

I’ve been a Sondheim fan ever since, particularly smitten with A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Pacific Overtures, Sweeney Todd, and Into the Woods.2 One thing’s for sure: the composer/lyricist doesn’t repeat himself. The variety and sheer weirdness of his productions speak to a restless mind able to range across an array of musical styles and tones. He frequently averred with a kind of sardonic twinkle he’d written only one hit song, “Send in the Clowns,” though the success of his musicals on film qualifies that claim.

Sondheim’s dominant tone is irony, the sometimes bitter, often painful, frequently comic discovery that what we take to be true is anything but. His plots turn on the sudden revelation of something half glimpsed and carefully repressed. He’s particularly good at the jarring discovery born of loss or confusion or mistaken belief.

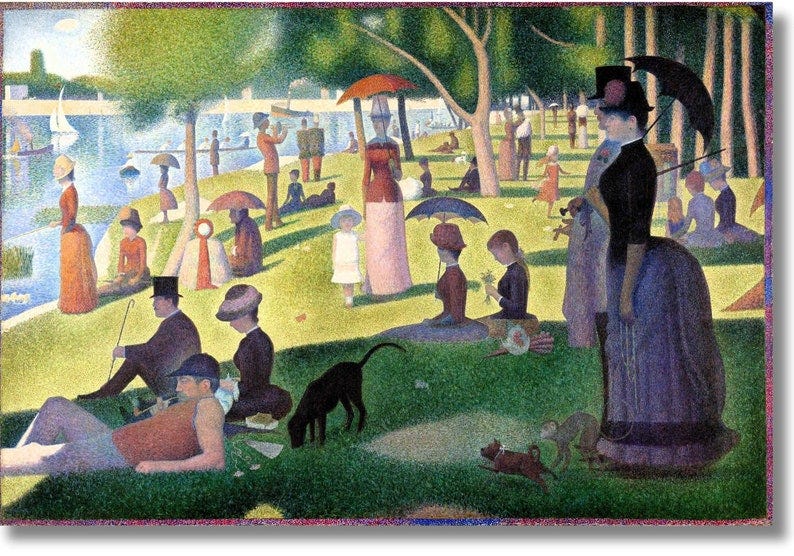

That’s hardly a recipe for comfort food at your local musical, but I’m addicted to it. And of all his plays Sunday in the Park with George remains my favorite, though I’ve never seen a live production. Sondheim, recovering from the devastating early close of Merrily We Roll Along, teamed up with James Lapine to imagine a truly counterintuitive project: Tell the story behind the making of George Seurat’s massive painting “Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.”3 Even after all these years it sounds like the recipe for a dull evening of theater.

Yet Lapine seems to have unlocked Sondheim’s creativity by pointing out the painting lacks the most interesting character: the artist himself. And so the writer/director and songwriter set about imagining how Seurat created his masterpiece and the price he paid for that effort. I suspect the French painter became Sondheim’s second self, a double to explore why one dedicates his talents to the frustrating, often isolating task of making art. It seems that after Merry’s collapse he needed to remind himself why he went through the heartbreak.

The result was memorable (even hummable) songs such as “Finishing the Hat,” “Putting It Together,” and “Move On.” As someone who tries to compose in words, I’m deeply moved by the play’s version of Seurat, rapt by his compulsion to execute his painting in the face of withering criticism, calls to the heart and desire, and the sheer banality of daily life. He persists—he finishes the hat.

When I rediscovered Sunday following Peters’ transcendent performance in A Little Night Music, Chris shared that the play doesn’t work for him as a whole. Yes, the first act is a triumph, but the second seems awkward and unconvincing. Watching the original production on YouTube I can see his point. Yet in a time of outright assault on the arts and humanities this play inspires me with its fierce devotion to creativity. We need our radical acts of creation now more than ever.

Despite the current administration’s disdain, even hatred for much that I believe in, I remind myself that the United States is a vast, wealthy country with a mature civil society. Even someone as willfully destructive as the current president cannot dismantle the network of nonprofits, cultural institutions, and state governments defending cherished values. I anticipate Trump’s hollowing out of federal agencies will require private and state funders to step up and for many of us to devise new funding and support strategies for the humanities and social justice. But like Seurat, we will persist. In this true clash of the titans, the President vs. American Civil Society, I’m placing my bet on the latter. We will collectively move on after the man-child has left the scene.

And so my heart rises in the middle of the night with the stirring chorus of “Sunday.” Time to get to New York City to see Audra Mcdonald in Gypsy, reputed to be the best musical ever written, with lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. . . .

In one of the fortuitous turns in American cultural history, Oscar Hammerstein became a surrogate father and mentor for young Sondheim. The protege’s rethinking of the musical emerged from a deep knowledge of the dominant practitioner of the form.

For a comprehensive and revelatory tour of Sondheim’s works, see his Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010) and Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981-2011) (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011).

Lapine tells the story of the musical’s origin, development, and production in the entertaining Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created Sunday in the Park with George (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).