There are some enterprises in which a careful disorderliness is the true method.

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

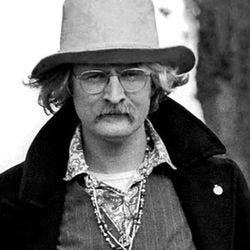

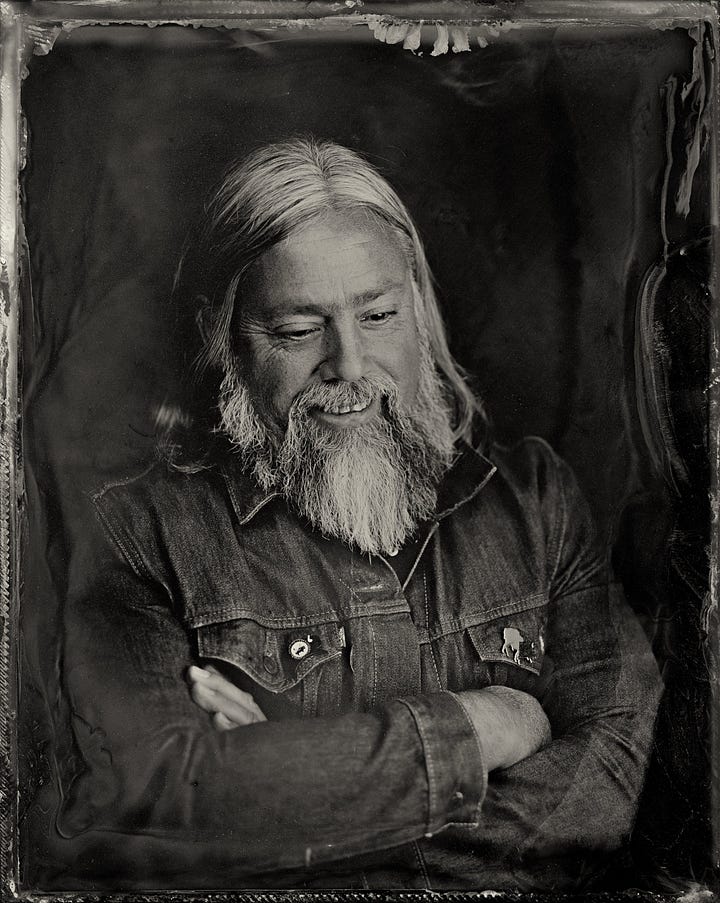

Richard Brautigan and Chris La Tray make for a strange pairing, one a long-dead avatar of late 60s/early 70s countercultural antics, the other a contemporary Native writer who responds to this messy world with memorable sentences and the story of finding his Indigenous family.

My method in the discovery and drafting phase of “Running Away to Montana” will be indirection, serendipity, and unexpected conjunctions. Unlike my previous book project, a biography of my Irish American great grandfather, a willful messiness and disorder seem appropriate. I have no idea what the final manuscript might look like, and right now, that’s liberating.

My current desire is to take on writers and lives largely ignored in my past writings on Montana and so, for the time being, few of the usual suspects from the state’s literary and political past will appear. One day I immerse myself in Ruth McLaughlin’s terribly sad homesteading story Bound Like Grass, the next Gary Ferguson’s sweeping, fun The Great Divide, the next John Clayton’s amusing, complex biography of Caroline Lockhart, the next a dip into friends’ personal narratives.

As my exploring unfolds I’ll test critical rubrics and would appreciate your honest appraisal of their usefulness. Do those terms help or hinder your understanding of the human beings under review? Here, for example, I’ll try out negative vs. positive freedom. D. H. Lawrence introduced this telling contrast in his irreverent Studies in Classic American Literature. He argued Americans are much better at running away from things (negative freedom) than at affirming a value or a way of life (positive freedom): “They came largely to get away—that most simple of motives. To get away. Away from what? In the long run, away from themselves. Away from everything. That's why most people have come to America, and still do come. To get away from everything they are and have been.” No wonder we’re so good at blowing things up and so poor at building sustainable institutions and communities. Is it possible Brautigan embodied negative freedom while La Tray is living out a positive version?

First call today: the “Montana Gang” centered in Paradise Valley (the spectacular region extending from Yellowstone Park’s northern entrance to Livingston). In truth I’ve been Missoula-centric most of my life, in part because I graduated from the University of Montana, in part because Richard Hugo’s confessional poetry swept me away during my undergraduate years, in part because the canon-defining Last Best Place Anthology emerged here.

When I traveled to Livingston in 2015 to read from Montana 1864 my hosts told me with conviction, “This town is every bit as important as Missoula when it comes to a literary life.” They have a point. Think Thomas McGuane, Jim Harrison, Tim Cahill, Richard Wheeler, William “Gatz” Hjortsberg, and the contemporary set that includes Doug Peacock, Marc Beaudin, Elise Atchison, Scott McMillion, Walter Kirn, and, just over Bozeman Pass, David and Betsy Quammen and Allen Morris Jones. I’ve long discounted this scene, perhaps because I’ve caricatured the original set as Hemingwayesque macho writers who seemed campy and anarchic (earnestness remains my enduring prop and pitfall).

Reading in rapid succession four memoirs/biographies of Brautigan has complicated that handy typecasting.1 I’ve come to believe the author of Trout Fishing in America was caught in the Hemingway jet stream while many of the other writers may have found a way through and around that trap. Hemingway offered young male writers a blend of masculine potency and the “effeminate” art of writing. As long as you killed animals, slept with lots of women, and demonstrated grace under pressure, you could pursue the writing life without fear of queerness. Even Hemingway’s suicide by a self-inflicted gunshot could appear glamorous since he had taken his ultimate fate into his own hands. Brautigan seemed to fall for all of it, including the often misogynistic treatment of women, and Montana seemed the ideal staging ground for living out that fantasy. Whether the entire Montana Gang did so will be cause for further reflection.

Brautigan was always the odd man out and that was his blessing and curse. He grew up in unrelieved poverty in the Northwest, beginning in Tacoma and ending up in Eugene, Oregon. He never knew his father (who disavowed his paternity); he moved from house to house, town to town so frequently his careful, rigorous biographer can hardly keep up; he was apparently beaten by step fathers and ridiculed as a poor kid. By his own account Brautigan suffered from dyslexia and so though mesmerized by books throughout his life, he struggled to read and write. In what seems a purely malicious act straight out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, authorities administered shock treatments to the twenty-year-old Brautigan, an atrocity with unimaginable consequences for his mental health.

By twenty-one he had seemingly escaped forever this dysfunctional youth, never reconnecting with his mother or step siblings. San Francisco, late 50s became his site of creating a new self. He migrated to the Beat set and became a fixture in the poetry and jazz scene. He made himself into a working writer, persistently generating poetry and prose. That daily ritual became his lodestar and for a time his salvation.

Biographies, it turns out, are often confessionals, and Hjortsberg’s 800-page blow-by-blow account of Brautigan’s troubled life seems especially so. Gatz was a link between the writer made suddenly famous and rich by Trout Fishing and the group of writers, actors, directors, and paramours drawn to Livingston by its natural beauty, fishing, hunting, and a quiet place to write. Gatz first met Brautigan during a reading at Stanford, then welcomed him when he flew north to Montana on a whim. McGuane must be seen as the star and magnet, tall, charismatic, a fine fisherman, a great storyteller, and for a time “Captain Berserko.” Brautigan invested his earnings from his wildly successful early publications in a “ranch,” really a forty-acre retreat in the shadow of the Absaroka Mountains. His neighbors included the Hjortsbergs, Fondas, and McGuanes (in various family configurations) and frequent guests came from San Francisco, Japan, Hawaii, and parts unknown. Since Brautigan never learned to drive, he had the perfect excuse to rely on others to take him to bars that became his all-too-frequent hangouts.

Why do some members of a raucous party crowd survive while others go down? That question seems to haunt not only Jubilee Hitchhiker but Greg Keeler’s harrowing account of their troubled friendship and Ianthe Brautigan’s deeply affecting memoir of her father’s life and death. Since Brautigan did not leave a suicide note survivors can only guess at its causes. His daughter blamed herself, as (I suspect) did both Hjortsberg and Keeler. What all witnesses make clear is that Brautigan never quite fit into the Montana scene. McGuane, in a reflective turn long after his friend’s death, may have put it best:

He was a unique character, what Melville would call an “isolato.” Richard was an anomaly because part of him was a very normal person, just a guy, who wanted to fish and hang around, but he was so strange with this high squeaky voice and bizarre costumes and appearance. He always struck me as somebody not entirely comfortable on earth. And then he had a celebrity following for a period of time . . . that he got addicted to and it was quite misleading because when they left him as they always do, I think he felt sort of bereft. . . . But he had terrible demons and was cruelly raised. So, I can’t judge him.2

While he had fished throughout his youth to put food on the table, Brautigan was never the technically sophisticated fly caster embodied by Jim Harrison and Russell Chatham. Yet he was drawn to what he took to be the “cowboy freedom” of the place. He could shoot clocks off walls and drink to all hours and leave dead animals to rot on the ground. As Keith Abbott points out with particular poignancy, a city boy left to his own devices in Paradise Valley had too much time on his hands, too few distractions, too few reasons not to drink himself into alcoholic rages and blackouts. While Ianthe movingly asserts that Montana’s beauty may have saved her father for a time, others’ testimony suggests he would have been better off had he never migrated to the state.

Chris La Tray’s story takes him into belonging. But to call his homecoming a Montana tale is misleading. This place demarcated by official political borders has been mapped and remapped by various cultures and La Tray homes in not to a state but to a people with deep history in a vast region that extends to Canada and North Dakota:

Atop the cliffs I can see people gathering for the powwow beneath a round framed arbor below. The structure provides shade, and the enclosed space in the middle, open to the sky, is for dancing. I feel a surge of emotion toward the tiny figures. We’re all a little lost, most of us anyway, and we’re coming together to reengage with who we are, what we’ve been. It’s slow going—we are all just people after all, many of us buffeted by generations of trauma—but we make the effort. I make the effort, even when the urge to stand apart from it all is just as present as love. To see my people, Indian people, gathered at the base of this particular landform to celebrate, to dance and drum and be thrilled, to be living among friends and family, is beautiful. . . . I take a breath. I’m part of this, part of them. I wipe the sweat from my brow and take a quick look around me for snakes. Then I follow the trail down the slope, across time, through genocide and diaspora, and fear and death and now rebirth, to food, to companionship, and increasingly, to community. (p.118)

Masculine status and behavior flow like leitmotifs through Becoming Little Shell. La Tray’s father denied his Chippewa identity and lived out the male code of quiet endurance and suffering. The writer must break through that deceptive front to discover his Little Shell relations. The story plays out as a weave of personal and ethnic knowledge, shifting back and forth between the author’s recovery of lost relatives and the Metis’s journey toward a homeland on the northern plains and formal recognition by the federal government.

The Montana of this account is full of prejudice, ignorance, and often stunning beauty. La Tray wants to understand not only his place among his unrecognized people but their place within this natural and social world:

I set out to write this book as a Little Shell person in service to my Little Shell people, but now I find myself a Little Shell person in service to the world. What we’ve faced . . . is something more and more people face every day. I have a responsibility to make sure all the stories related to this struggle are told. I feel the light hands of my ancestors at my back, urging me forward, and they’re with me when I falter and question the use of it all. It’s hard.

But it’s also a beautiful, beautiful life to be living. (p. 271)

La Tray’s remarkable skill at recording overlooked and elusive moments of grace—captured in his quirky, moving One-Sentence Journal—serves him well as he recounts journeys to places central to his people’s history and culture such as Lewistown and Chouteau, Montana, and Pembina, North Dakota. If Brautigan appears ever adrift in a world whose masculinist code offered little belonging or purpose, La Tray seems ever more in place among the Little Shell. While the 60s author came to Montana in flight from his past and his pain, the contemporary writer moves ever closer to something sustaining.

Perhaps I should at long last confess to another difference between these two writers: While I’ve never cottoned to Brautigan’s brand of countercultural play, La Tray is one of my favorite current writers. Trout Fishing in America has always read to me as Vonnegut Lite, clever in its own way but lacking the soul and meaning of more enduring postmodern narratives. La Tray, on the other hand, writes with a directness and honesty that reminds us literature can help readers see the world in all its complexity, hurt, and specificity. The reader can be brought home through narrative magic. Perhaps it should not surprise that a writer who has found his people can offer that elixir while one so far from a confident place in the world cannot.

Keith Abbott, Downstream from Trout Fishing in America: A Memoir of Richard Brautigan, ca. 1989 (Vermillion: Astrophil, 2009); Ianthe Brautigan, You Can’t Catch Death: A Daughter’s Memoir (New York: St. Martin’s/Griffin, 2000); Greg Keeler, Waltzing with the Captain: Remembering Richard Brautigan (Boise: Limberlost, 2004); William Hjortsberg, Jubilee Hitchhiker: The Life and Times of Richard Brautigan (Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2012).

Beef Torrey, Conversations with Thomas McGuane (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007), p. 199.

Hey, thanks for the shout-out! I totally agree about negative/positive freedom, a theme I explored (with less eloquence) in Small Town Bound. Keep up the good work!